Primary Progressive Apraxia of Speech

Description

- Primary Progressive Apraxia of Speech (PPAOS) is a neurodegenerative disease affecting the planning and programming of movements necessary to speech production (Botha, H., & Josephs, K. A., 2019). This disorder is characterized by articulatory errors (additions, distortions) and prosodic impairments (slow and segmented speech). It can also be difficult for the patient to initiate speech.

- The onset of the disease is progressive and initially affects speech predominantly. PPAOS must be suspected for every patient with an evolutionary speech disorder.

- Men and women are equally affected. Also, no environmental, socioeconomics or educational factors have been linked to the disease (Duffy, J. R., Utianski, R. L., & Josephs, K. A., 2020).

- A positive family history for neurodegenerative disease is found in 25% of patients diagnosed with PPAOS (Duffy, J. R., Utianski, R. L., & Josephs, K. A., 2020).

- PPAOS is a rare neurodegenerative disease and no study has yet looked into its prevalence. However, it can be estimated at 4.4 per 100,000 (Botha, H., & Josephs, K. A., 2019).

Here is a video clip of a man with Primary Progressive Apraxia of Speech (in French Only) :

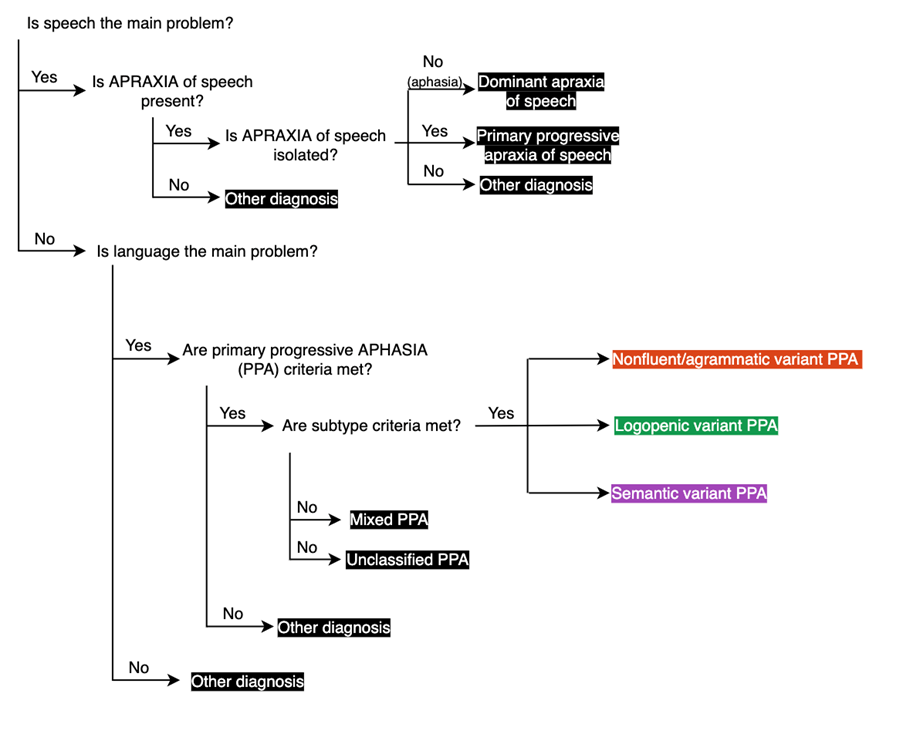

Diagnostic criteria (Based on Botha, H., & Josephs, K. A., 2019)The main complaint reported is: “I know what to say, but I can’t get it out”. |

|---|

| Inclusion |

|

| Exclusion |

|

APRAXIA of speech tends to remain the predominant symptom when the disease progresses, but other neurodegenerative impairments may also emerge such as motor, language and behavioral disturbances.

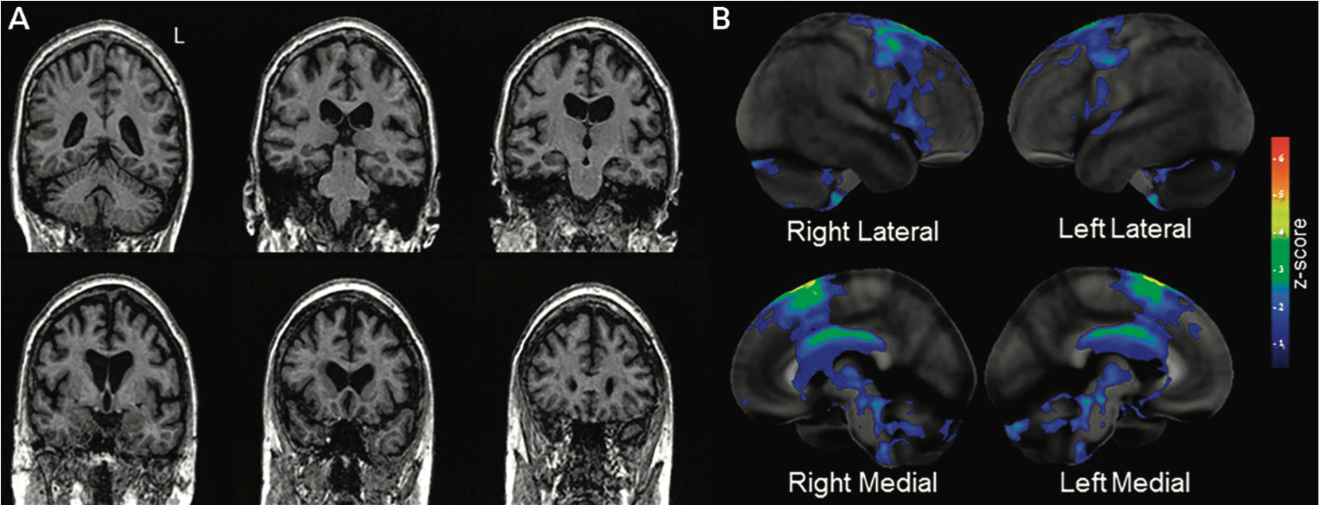

Neuroimaging

Imaging with functional MRI as well as 18F‑fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG‑PET) demonstrates two very focal and precise areas involved in the disease when APRAXIA of speech is the only or predominant symptom: superior premotor and supplementary motor cortex. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) shows a focal white matter tract degeneration underneath the grey matter atrophy and in the body of the corpus callosum (Josephs, K. A. et al., 2014).

As mentioned, PPAOS doesn’t affect language. Therefore, the inferior frontal gyrus and lateral temporal areas, both responsible for language, are initially spared (Botha, H., & Josephs, K. A., 2019).

Subtypes

There are three main subtypes in primary progressive APRAXIA of speech:

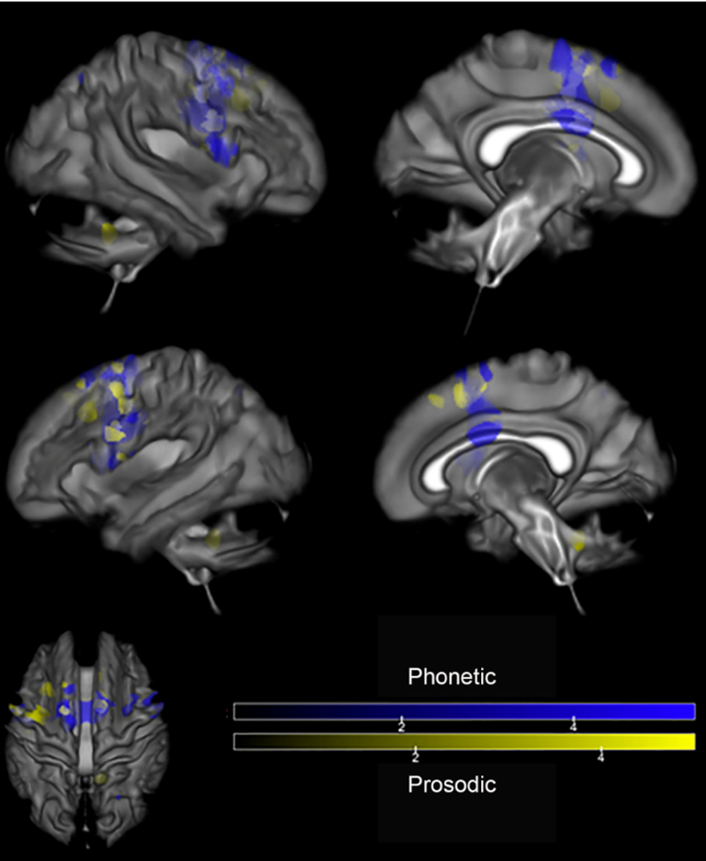

- The phonetic subtype is characterized by distorted speech (e.g. catastrophe → catatophe) and additions (e.g. apple → papple).

- The prosodic subtype is characterized by slow rate and segmented speech.

- When neither of the two subtypes predominates or when speech is too severely impaired to assess the subtypes, the subtype is referred to as mixed (Utianski, R. L. et al., 2018).

There is very little research and information about the subtypes, their first symptoms, and evolution, but it is known that the predominant subtype at the time of the first assessment has prognostic value and affects the evolution of the disease. The prosodic subtype is associated with a faster progression and more aggressive evolution of the disease to a supranuclear palsy (Utianski, R. L. et al., 2018). These patients also show earlier onset and faster-declining parkinsonism. On the other hand, the phonetic subtype is associated with a faster-progressing motor speech impairment and more severe aphasia (Whitwell et al., 2017).

Both subtypes show atrophy in the supplementary motor cortex (SMA). When imaging with MRI, the prosodic subtype demonstrates focal atrophy of the SMA, whereas the Phonetic subtype shows additional atrophy in the prefrontal cortex and cerebellum.

DTI highlights bilateral atrophy of the SMA for the Phonetic subtype that extends bilaterally to the superior frontal area, the body of the corpus callosum, and the cingulum. Prosodic subtype shows atrophy in the right superior cerebellar peduncle.

Finally, imaging with FDG-PET indicates hypometabolism in the SMA for both subtypes, along with hypometabolism in the superior frontal regions bilaterally, insular region, and in the cerebellum for the Phonetic subtype (Utianski, R. L. et al., 2018).

Other signs and symptoms

Primary progressive APRAXIA of speech is often associated with non-verbal oral apraxia, which is described as the difficulty to perform nonspeech movements involving the face, mouth, or larynx. Approximately 2/3 of PPAOS patients present non-verbal oral apraxia. When suspected, it can be demonstrated by asking the patient to mimic simple movements such as: blowing, puffing out the cheeks, whistling, and sticking out the tongue (Botha, H., & Josephs, K. A., 2019).

Regarding behavioral aspects, transient changes can be noted throughout the disease. Based on a data collection at the Clinique interdisciplinaire de mémoire du CHU de Québec (CIME), the most common behavioral changes are anxiety, irritability, and loss of inhibition.

Preliminary data collected in our clinical setting suggests that executive functions (EF) are often impaired upon diagnosis of the disease. Given that patients consult on average just a little over two years after the onset of the disease, it’s possible to say that this symptom emerges after approximately 2-3 years of evolution. Oppositely, some studies don’t mention changes regarding EF with the evolution of PPAOS or mention that they are well preserved. Note that nor the presence or absence of EF impairment is a diagnostic criteria for PPAOS. Nevertheless, its presence is likely since EF are closely linked to the prefrontal cortex. All in all, it can be demonstrated by a variety of tests such as the clock-drawing test, Luria’s test, the pentagon drawing test and counting backward (100-7). Another sign of an EF impairment is perseverance during cognitive assessment.

Yes/no reversal is another possible sign, although it is rare (Josephs, K. A. et al., 2014).

Some cognitive functions remain mostly preserved throughout the evolution of PPAOS:

- Memory

- Visuospatial function

- Comprehension

- Gnosis

Primary progressive APRAXIA of speech’s evolution over time

Long-term evolution is unknown in PPAOS patients. Some develop frontal lobe disorders (executive functions, behavior disorders). However, no linear evolution has been described with this disease and there is a notable heterogeneity within patients. Generally, patients with PPAOS progress much slower than patients with primary progressive APHASIA (PPA).

Signs of parkinsonism such as rigidity with contralateral activation (Froment’s maneuver), slowed finger movements, and reduced spontaneous movements are often present 2 to 3 years into the illness. The most common signs are bradykinesia and facial masking. Ideomotor apraxia can also coexist with the onset of parkinsonism (Botha, H., & Josephs, K. A., 2019; Josephs, K. A. et al., 2014).

PPAOS is part of a variety of diseases called tauopathies. It often tends to progress into a progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) or a corticobasal syndrome (CBS) (Utianski, R. L. et al., 2018), which are Parkinsonian disorders. PSP is characterized by stiffness, falls, pseudobulbar palsy, vertical gaze palsy, dysphagia, cognitive impairment and personality change. CBS combines cortical impairments such as apraxia, agraphesthesia, astereognosis to movement disorder (stiffness, dystonia, myoclonus).

Rarely, PPAOS progresses into amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). The evolution of this variant is not well known, but this variant is expected to progress more quickly, given the more aggressive nature of ALS.

APRAXIA of speech is expected to be the predominant symptom throughout the course of the disease. Initially, difficulties may be limited to long and articulatory complex words.To compensate, speech is slow rated and segmented. Eventually, simpler words will also be more difficult to pronounce, and then the disease will progress to complete mutism (7 to 10 years after the onset of symptoms; Duffy, J. R., Utianski, R. L., & Josephs, K. A., 2020).

Generally, patients do not develop any difficulty in activities of daily living (ex. toileting, dressing) and home living activities (ex. cooking, maintenance, finances, etc.). However, based on data collected at the CIME, it’s not unlikely to develop certain difficulties in these activities throughout the disease. Moreover, a lot of patients reported that their speech difficulties brought them to retire early, altered their daily living activities, and reduced their social interactions (Utianski, R. L. et al., 2018).

A majority of patients will develop dysphagia with choking episodes. Dysphagia is usually more evident with the consumption of liquids (Josephs, K. A. et al., 2014).

As the disease progresses, the frontal lobe degeneration can lead to behavior changes, primitive reflexes emergence, and executive functions impairments (Utianski, R. L. et al., 2018; CIME data, 2020).

The evolution of primary progressive APRAXIA of speech can also lead to urinary incontinence, dysarthria (spastic or hypokinetic), aphasia and agrammatism (mostly in writing; Botha, H., & Josephs, K. A., 2019). Praxis, oral apraxia, dysarthria are also expected to worsen, in addition to the progression of parkinsonism, leading to postural instability and falls (Josephs, K. A. et al., 2014).

Primary progressive APRAXIA of speech (PPAOS) vs non-fluent/agrammatic variant of primary progressive APHASIA (nfvPPA)

Unlike the non-fluent/agrammatic variant of PPA, it’s very rare for agrammatism to be present in PPAOS. As mentioned, in PPAOS, speech is altered and hesitant, but language (lexical access, reading, writing, grammar, comprehension) and memory are generally well preserved.

Some characteristics are often present in both neurodegenerative diseases:

- Yes/no reversals

- Non-verbal oral apraxia

- Parkinsonism

How to detect PPAOS

It’s important to take into account that cognitive tests such as MoCA and MMSE are generally successful in patients with primary progressive APRAXIA of speech and scores do not tend to drop drastically with the disease’s progression (CIME data, 2020). However, to allow a more valid cognitive assessment, written answers should be encouraged due to speech impairment.

The diagnosis of PPAOS needs to test all functions related to language to distinguish a speech impairment (ex. PPAOS) from a language disorder (ex. non-fluent/agrammatic variant of PPA).

Reminder: Language vs Speech |

|---|

| Language |

Language includes multiple functions:

|

| Speech |

Neuromuscular execution of language: the act of talking.

|

In case of doubt, a complete evaluation with a speech-language pathologist can help to establish a clear differential diagnosis.

For the complete screening sequence for language or speech disorders, refer to the section "I am a healthcare physician and I would like to detect a PPA"

Throughout the evaluation, mostly in spontaneous speech, note the presence of:

- Distortions or additions (e.g. catastrophe → castrophe)

- Difficulty pronouncing or articulating words

- Speech blocks

- Slow rated and segmented speech

- Phonetic or semantic paraphasias (e.g. pear → apple)

As mentioned, the underlying pathology in PPAOS is generally a tauopathy. Therefore, it’s essential to question and evaluate changes in the motor sphere that could indicate parkinsonism:

- Bradykinesia

- Slowed down walk

- Parkinsonian gait (smaller support polygon, festinating, stooped posture, etc.)

- Falls

- Facial masking

- Stiffness

Overall, language should be well preserved. However, speech can be slowed and segmented, and/or filled with articulatory errors (additions, distortions).

Patient management by the primary care physician

For the complete initial care, refer to “Patient management by the primary care physician”.

After detecting a speech disorder in a patient, it is suggested to refer the patient to speech therapy. In the case of primary progressive APRAXIA of speech, the main role of the speech-language pathologist will be to plan/introduce an augmentative and alternative communication method (ex: use of an electronic tablet, pictograms/symbols, written communication, etc.). To allow optimal care, it is essential to refer the patient as early as possible in the course of the disease.

There is currently no curative pharmacological treatment. However, the psychological dimension of the disease is very important. The family doctor should explore the psychosocial sphere of the disease as speech disorders can lead to isolation and anxiety in patients.

References

- Botha, H., & Josephs, K. A. (2019). Primary Progressive Aphasias and Apraxia of Speech. Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.), 25(1), 101–127. – https://doi-org.acces.bibl.ulaval.ca/10.1212/CON.0000000000000699.

- Duffy, J. R., Utianski, R. L., & Josephs, K. A. (2020). Primary progressive apraxia of speech: from recognition to diagnosis and care. Aphasiology, 1-32. – https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2020.1787732.

- Josephs, K. A., Duffy, J. R., Strand, E. A., Machulda, M. M., Senjem, M. L., Gunter, J. L., Schwarz, C. G., Reid, R. I., Spychalla, A. J., Lowe, V. J., Jack, C. R., Jr, & Whitwell, J. L. (2014). The evolution of primary progressive apraxia of speech. Brain : a journal of neurology, 137(Pt 10), 2783–2795. – https://doi-org.acces.bibl.ulaval.ca/10.1093/brain/awu223.

- Clinical Progression in Four Cases of Primary Progressive Apraxia of Speech. American journal of speech-language pathology, 27(4), 1303–1318. – https://doi-org.acces.bibl.ulaval.ca/10.1044/2018_AJSLP-17-0227.

- Utianski, R. L., Duffy, J. R., Clark, H. M., Strand, E. A., Botha, H., Schwarz, C. G., Machulda, M. M., Senjem, M. L., Spychalla, A. J., Jack, C. R., Jr, Petersen, R. C., Lowe, V. J., Whitwell, J. L., & Josephs, K. A. (2018). Prosodic and phonetic subtypes of primary progressive apraxia of speech. Brain and language, 184, 54–65. – https://doi-org.acces.bibl.ulaval.ca/10.1016/j.bandl.2018.06.004.